Contents:

Cybersecurity researchers from Sentinel Labs have recently released a new in-depth study of ShadowPad, a Windows backdoor that enables threat actors to download further malicious modules or exfiltrate sensitive information.

According to SentinelOne researchers Yi-Jhen Hsieh and Joey Chen,

The adoption of ShadowPad significantly reduces the costs of development and maintenance for threat actors. We observed that some threat groups stopped developing their own backdoors after they gained access to ShadowPad.

As a successor to PlugX and a modular malware platform since 2015, ShadowPad has drawn attention back in 2017 in the wake of supply-chain incidents targeting NetSarang, CCleaner, and ASUS. Its operators managed to shift techniques and update their defensive measures with advanced anti-detection and persistence tactics.

According to The Hacker News, attacks involving ShadowPad have troubled organizations in Hong Kong and critical infrastructure in India, Pakistan, and other Central Asian countries. Although primarily attributed to APT41, the malware is known to be preferred by several Chinese espionage actors like Tick, RedEcho, RedFoxtrot, and clusters dubbed Operation Redbonus, Redkanku, and Fishmonger.

Back in 2019, the actors used a special version of ShadowPad which allowed them to generate samples with a handful of plugins embedded by default24. In 2020, they gained access to a new version of ShadowPad which had updates and more advanced obfuscation techniques. They are now using it and another backdoor called Spyder25 as their primary backdoors for long-term monitoring26, while they distribute other first-stage backdoors for initial infections including FunnySwitch, BIOPASS RAT27, and Cobalt Strike. The victims include universities, governments, media sector companies, technology companies, and health organizations conducting COVID-19 research in Hong Kong, Taiwan, India, and the US.

ShadowPad M.O.

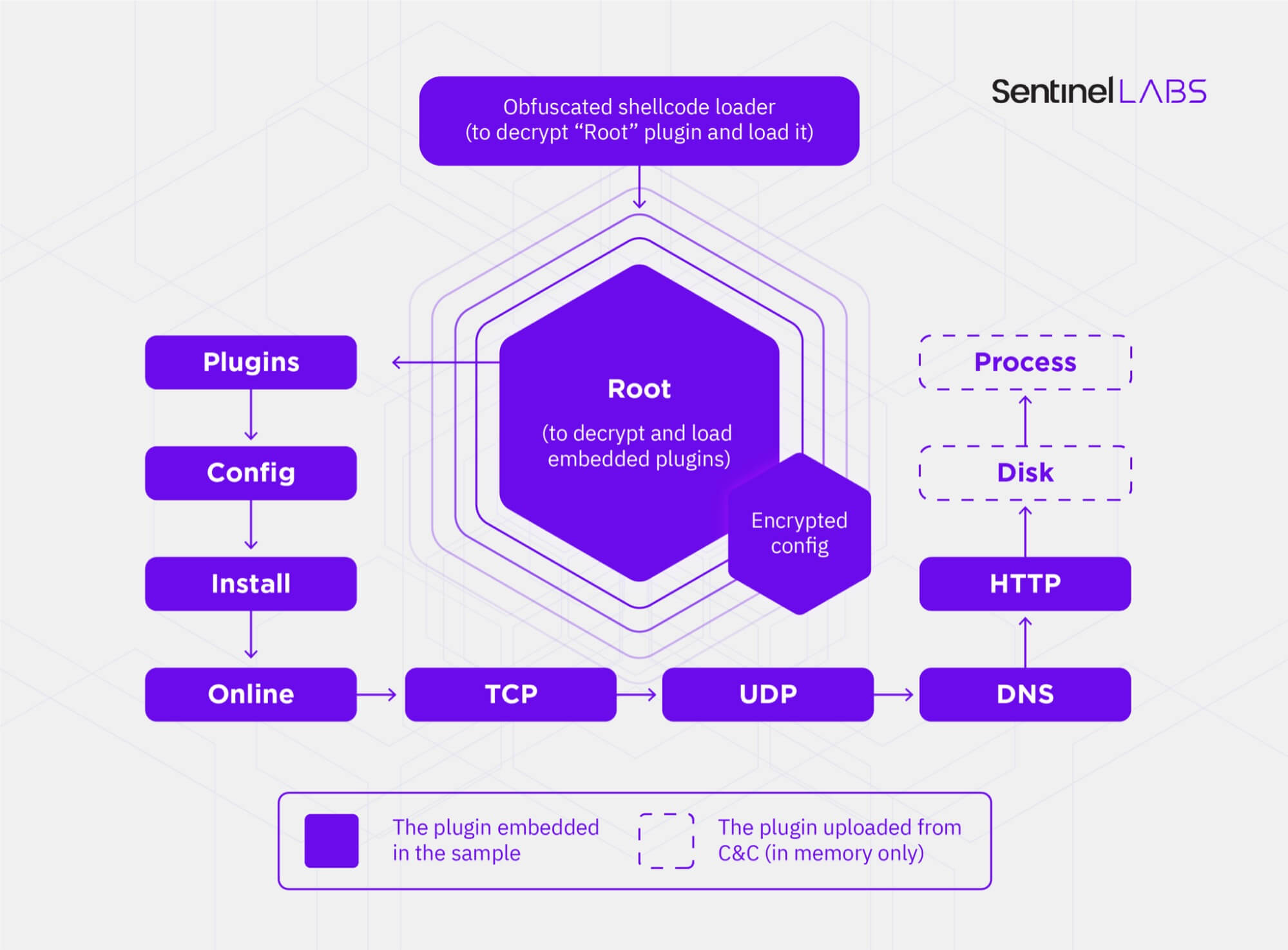

ShadowPad operates by decrypting and loading a Root plugin in memory, which takes care of loading other embedded modules during runtime. Additionally, it dynamically deploys other plugins from a remote command-and-control (C2) server, allowing threat actors to add extra functionality not built into the malware by default. According to the researchers, so far 22 unique plugins have been identified.

The infected devices are commandeered by a Delphi-based controller that’s used for backdoor communications, updating the C2 infrastructure, and managing the plugins.

What’s more, the feature set made available to ShadowPad users is not only controlled by its seller but each plugin is sold separately. The adoption of the “sold – or cracked – commercial backdoor” raises difficulties for security researchers in ascertaining which malicious actor they are investigating.

Any claim made publicly on the attribution of ShadowPad users requires careful validation and strong evidentiary support so that it can help the community’s effort in identifying Chinese espionage. For these threat actors, using ShadowPad as the primary backdoor significantly reduces the costs of development.

The emergence of ShadowPad, a privately sold, well-developed, and functional backdoor, offers threat actors a good opportunity to move away from self-developed backdoors. While it is well-designed and highly likely to be produced by an experienced malware developer, both its functionalities and its anti-forensics capabilities are under active development.

Network Security

Network Security

Vulnerability Management

Vulnerability Management

Privileged Access Management

Privileged Access Management  Endpoint Security

Endpoint Security

Threat Hunting

Threat Hunting

Unified Endpoint Management

Unified Endpoint Management

Email & Collaboration Security

Email & Collaboration Security