Contents:

A new phishing kit, “File Archivers in the Browser” abuses ZIP domains. The kit displays bogus WinRAR or Windows File Explorer windows in the browser. The goal is to convince users to launch malicious processes.

Google just enabled this month a new feature that allows websites and emails to register ZIP TLD domains. For example, such a domain would be “heimdalsecurity.zip.

Weaponizing ZIP TLD Domains

Researchers are debating if ZIP TLD domains are a security risk or not. The main threat is that some websites will convert strings like “example.zip” into a link. This way cybercriminals could easily use it for malware delivery or phishing attacks.

For example, if you send someone instructions on downloading a file called setup.zip, Twitter will automatically turn setup.zip into a link, making people think they should click on it to download the file.

When you click on that link, your browser will attempt to open the https://setup.zip site, which could redirect you to another site, show an HTML page, or prompt you to download a file.

Nevertheless, you must first persuade a user to open a file, which might be difficult, just like with any virus delivery.

How the Phishing Kit Works

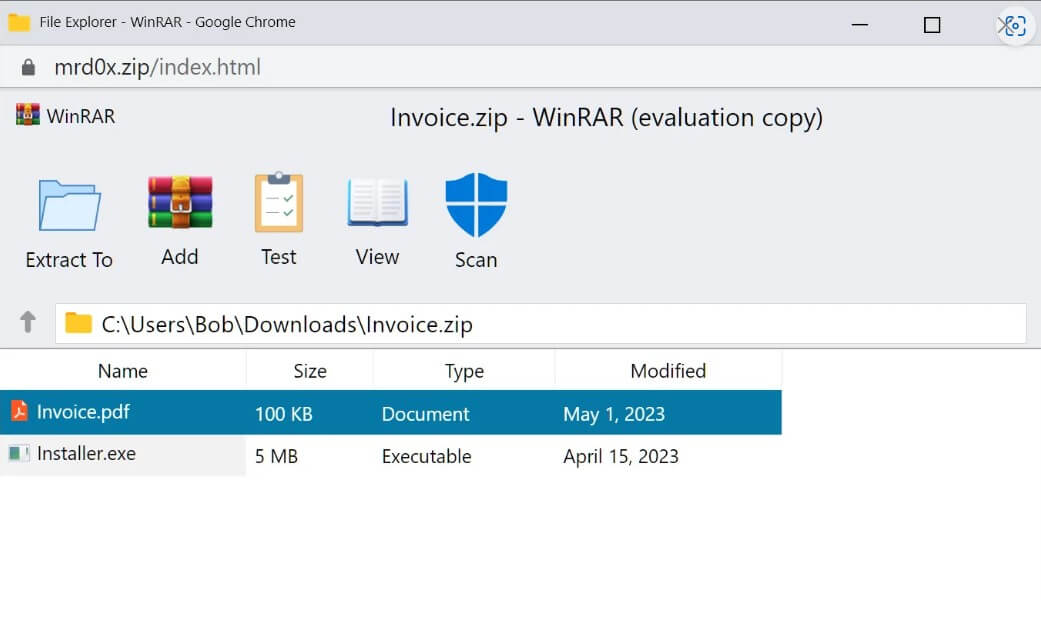

Security researcher mr.d0x built a phishing kit able to create fake in-browser WinRar archives and File Explorer Windows. Both are shown as ZIP domains to make users believe that they are .zip files.

When a .zip domain is opened, the toolkit will embed a false WinRar window in the browser. This will give the impression that the user has opened a ZIP archive and is now viewing the files inside it.

To make it appear more like a WinRar window displayed on the screen, the address bar and scrollbar from the popup window can be removed. The creator of this kit also put in place a phony security scan button that, when clicked, claims that the files were scanned and no risks were found.

Using the Phishing Kit for Malware

Cybercriminals can leverage this phishing toolkit for stealing credentials and spread malware, for example.

Double-clicking a PDF in the bogus WinRar window can send the user to a different page that requests login information in order to view the file correctly.

The toolkit can also be used to deliver malware by displaying a PDF file that downloads a similarly named .exe instead when clicked. For example, the fake archive window could show a document.pdf file, but when clicked, the browser downloads document.pdf.exe.

The victim will see just a harmless PDF in its downloads folder. As Windows doesn’t show file extensions, the de user might click on it, not knowing it is executable.

When searching for files on Windows, if that file is not found, the system opens a searched-for string in a browser. The website will open if that string is a valid domain name; otherwise, Bing search results will be displayed. Cybercriminals can leverage this by registering a zip domain named as a common file name, and Windows will open the site in the browser automatically when someone searches for it on the operating system.

If that site hosted the ‘File Archivers in the Browser’ phishing kit, it could trick a user into thinking WinRar displayed an actual ZIP archive. This technique illustrates how ZIP domains can be abused to create clever phishing attacks and malware delivery or credential theft.

If you liked this article, follow us on LinkedIn, Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube for more cybersecurity news and topics.

Network Security

Network Security

Vulnerability Management

Vulnerability Management

Privileged Access Management

Privileged Access Management  Endpoint Security

Endpoint Security

Threat Hunting

Threat Hunting

Unified Endpoint Management

Unified Endpoint Management

Email & Collaboration Security

Email & Collaboration Security